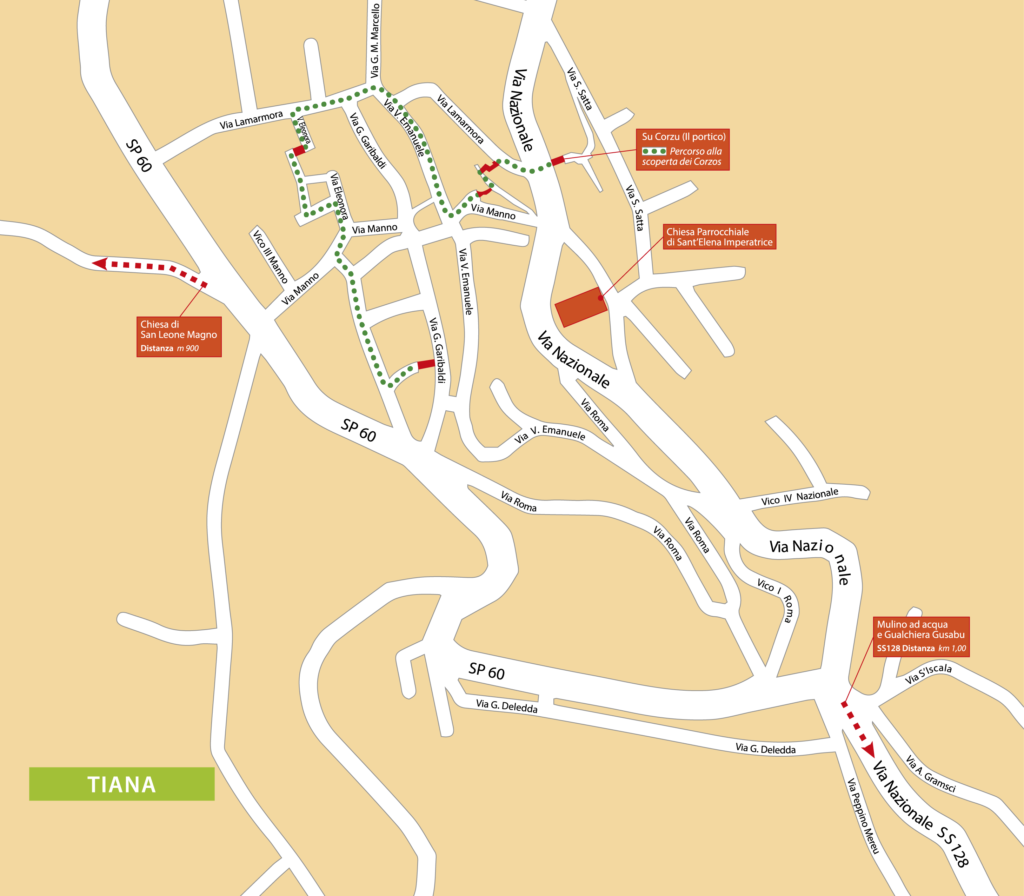

Gusabu fulling mill

The fulling mill (‘gualchiera’), known as cracchera in Sardinian, was a facility for processing wool from which, through the process of fulling and subsequent felting, orbace (Sardinian woollen fabric) was produced. This was a coarse, extremely hard-wearing fabric used to make the clothes in use on the island until the late 1940s.

The mechanism with which the wool was processed consisted of large wooden hammers that, thanks to the force of the water, beat the wet fabric over a long period of time in order to refine it and make it compact.

Orbace was a durable and waterproof fabric, indispensable to people like shepherds and farmers, who spent much of their time outdoors, exposed to the elements and in need of clothing that could withstand tearing and rubbing against vegetation and rocks.

Originally, in the village of Tiana, along the course of the Rio Tino, there were dozens of fulling mills that worked constantly, summer and winter, causing a loud and continuous noise. Throughout the year, wool woven by women from Barbagia, Nuoro and Mandrolisai was brought to the village, feeding a real production chain.

During the two world wars, in particular, the demand for orbace was very high due to the need for soldiers’ uniforms, but by the post-war period, there remained only two active fulling mills. By the 1970s, the last facility had also been closed, because by then orbace production was no longer in demand, having been totally superseded by industrial textile production.

The fulling mill now in operation originally belonged to the Zedda family, the last to cease this activity, and was acquired as a public asset thanks to the local institutions that understood the importance of preserving this structure, for the preservation of the memory of their community. Once taken over, the mill was restored and put into operation for educational and tourist purposes.

In addition, an artificial pond was built upstream of the plant at the behest of the municipal administration, to ensure the operation of the machinery even in summer, when the river’s water flow is greatly reduced.

Text by Laura Melis

BIM TALORO

BIM TALORO